7. Resisting toxic pesticides in Kenya

“Peasants and other people working in rural areas have the right not to use or to be exposed to hazardous substances or toxic chemicals, including agrochemicals or agricultural or industrial pollutants”.

Agriculture dominates the Kenyan economy, which employs 70% of the rural population, and accounts for around 33% of its GDP.111

Land is an important factor in food production, including the local population’s accessibility to it, an important issue in Kenya since 1895, when the country was declared a British protectorate. A series of laws to grab land from the local population were implemented by the British, with freeholds sold and leases granted instead for up to 99 years. Upon decolonisation in 1963, Kenya inherited these same land laws and policies, created to grab large parts of land for the British Crown, with the land grabbed (used for different purposes, from agriculture, to mining to game reserves) transferred to the government of Kenya.

Local populations that used and lived on these lands as pastoralists, peasants, hunters, gatherers, and fisherfolk were effectively displaced and turned into squatters on their own land. These lands were never returned to the original inhabitants, and instead were sold or leased to corporations and other foreign and national landowners for different development purposes. With the failure of the new post-independence Kenyan government to redress the land issue, local communities had to move to urban areas, mostly populating new informal settlements and increasing food insecurity across the country.

The ownership of land and land distribution for peasants to grow food is now one of the most important challenges for the country. Today, Kenya is highly dependent on export-oriented farming, whilst at the same time relying on imports of other essential crops from abroad.112

Kenya’s export-oriented agricultural model is wrapped up with the trap of foreign debt: agricultural exports provide the foreign currency needed to pay down foreign debt. In 2020, the total foreign debt of Kenya rose to around US$38 billion, up from US$8.5 billion in 2010.113

If a country such as Kenya fails to honour its debt obligations to foreign lenders, it must negotiate for either an extension of the deadline or ask for debt service relief (debt suspension). Free trade agreements are often negotiated at this point, which traditionally covered taxes and tariffs between two countries, but in recent decades have specifically been designed to break down ‘non-tariff barriers’ to trade: environmental, social, and labour standards. Trade and debt are closely connected,114

as agreements are usually signed in favour of the lending country, and often include clauses permitting imports of products banned in the country of origin, such as agrotoxins, poisonous pesticides and toxic herbicides like paraquat.115

Trade deals favour Global North corporate interests, with devastating consequences for communities in the Global South.

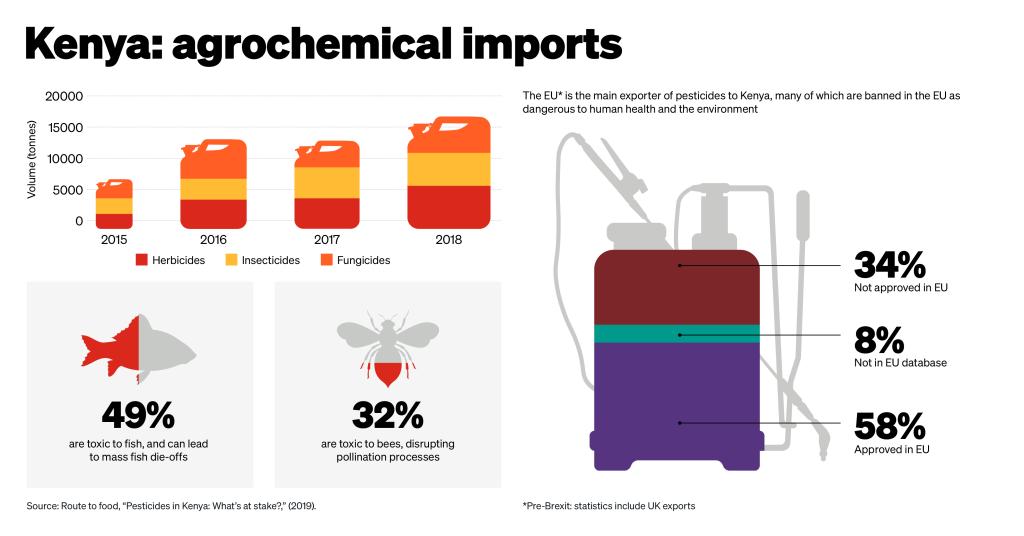

Many of the pesticides sold on the Kenyan market are mutagenic (they change the DNA of a cell), are endocrine disruptors (interfere with human hormones), are carcinogenic, or have a detrimental effect on the reproductive system.

Oxyflourfen and glufosinate-ammonium are toxic herbicides withdrawn from the European market which are registered as ingredients in 12 different commercial pesticides for sale in Kenya.116

Paraquat is another herbicide banned in the EU and the UK but widely available in Kenya. It is imported by Syngenta Kenya Ltd., a subsidiary of Syngenta, which also owns one of the largest paraquat-manufacturing factories in Europe, based in Huddersfield, England. Workers and farmers who regularly come into contact with paraquat have reported severe health problems, including impaired lung function, skin disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases.117

The recommended dosage and application of paraquat widely varies from how it is actually used in Kenyan agriculture, increasing the risks associated with its use. The pesticide was originally designed for use in megafarms where the application process was done at some distance. This is not the case in small farms of less than two acres (approximately 0.81 hectares), which are widespread in the Kenyan countryside.

Building the alternatives through peasant agroecology and popular education.

“Peasants and other people working in rural areas have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their own seeds and traditional knowledge”.

War on Want’s partner, the Kenyan Peasants League (KPL), is campaigning to stop the import of banned pesticides from the UK and EU, while advocating for organic pesticides and agroecological training schools.

Throughout 2022, KPL organised smallholder farmers into farming collectives of between 20 and 50 individuals, in the aim of reviving local markets and indigenous seeds, including through the establishment of area-based and household seed banks. Peasant farmers now have the independence and ability to store and reproduce their own seeds every season and use affordable and safe pesticides on their crops.

When the soils are healthy, then the human beings and animals will be healthy. The health of the soils is affected by the use of chemical pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers that kill the soil microorganisms, leaving the soil bare and meaning that the farmers have no options but to use them over and over again, putting them into a vicious cycle of dependency”.

Since 2020, in partnership with War on Want KPL has been working on a project to test two organic pesticides, which will then be distributed to KPL members and other farmers as alternative, affordable, and safe solutions to agrotoxins. The first formulation was developed at the University of Graz in Austria, with the second developed by a local farmer and member of the KPL. The first phase of the project, with field tests across the counties of Baringo, Migori, Nairobi and Machakos, produced promising results.118

Dick Olela, National Convener of the KPL, said that both organic formulations were successful in stopping aphids from attacking vegetables:

We sprayed the leaves of kales infested by aphids, and after one week the aphids were already cleared and the leaves turned green and healthy”.

Both organic formulations are now being tested on maize and other plants.

A second phase of the project is now underway to produce and distribute the active ingredients of the organic pesticide to 30 peasant farmers across both Migori and Baringo counties, while holding farmer education and consultative forums with 200 peasant farmers.

KPL is running a national campaign to ban the import of agrotoxins and expose how highly profitable these imports are for the Kenyan government and Global North corporate exporters. The campaign is also pushing for the legal registration of organic pesticides in Kenya, to clear the path for mass production.

They have done a lot of comparison work here, and the plots that have actually been planted using organic manure are performing far much better. And that's why I am certain that we as KPL are winning...we are on the right track. When we started, we were very few, but you see...the movement has since grown bigger. We have had many clusters, getting formed day after day and the indigenous seeds are in demand from a wider population across Kenya."