What about the jobs?

We did not tell you to come here. You came here, not to do charity through the industry, but because you know that you can pay less and make more profit. And now you have enough profit and are thinking okay, we don’t care whatever happens to them, we’ll just go away. It’s not right – the workers’ voice should be included. We should have our space whenever decisions are being made.”

The fashion industry is a driver of poverty, debt and stark inequality – and a major cause of ecological and climate damage. This must change, but how?

These social and environmental crimes have the same systemic causes, yet in some quarters the debate on how we change the fashion industry has become polarised between ‘workers’ and ‘planet’.

Environmental movements call for consumption to be drastically reduced or ended for the sake of the planet – people must buy better, shop less, or not shop for clothing at all – while factory jobs are written off as dull, dangerous, short-term, and cheap.

In return, economic justice and workers’ rights movements highlight the impact of this reduction on people, communities, and national economies across the Global South: millions of job losses and the undermining of the fight for decent working conditions.

If we do not bridge the two key imperatives of environmental and economic justice – care for the planet and workers’ rights – there is a high risk that policies designed to reduce environmental impacts will further harm the rights and livelihoods of millions of farmers and workers in fashion supply chains.

At worst, some proposed environmental ‘solutions’ to radically reduce the fashion industry’s carbon footprint – such as consumers simply buying less – risk devastating consequences for millions of people in the Global South, particularly Black and Brown migrant women and their communities. Such proposals threaten to replicate the patterns of so-called sacrifice zones, whereby geographical areas are consigned to permanent economic disinvestment and environmental disaster in order for others to benefit.

As well as being ethically untenable, such approaches severely limit the public support needed for a transition to become a politically viable possibility, while making useful material for populist politicians who seek to stoke up reactionary feeling to slow down or stop any kind of environmental transition.

The intentional co-option of human rights narratives also serves to protect big fashion’s interests. In 2019, Karl-Johan Perrson, CEO of H&M, gave an interview in which he stated that while shaming fashion consumers “may lead to a small environmental impact, it will have terrible social consequences.” 18

The idea that H&M is on the side of workers, rather than primarily concerned with its own profit margins, jars with the regular exposés of gender-based violence, stolen wages, and labour rights violations in H&M supply chains.19

But by expressing concern for factory jobs if clothing production drops, Perrson is able to exploit the tension that exists between environmental campaigners, people scared to lose their livelihoods, and politicians fearful of falling popularity, to push back against environmental pressure.

Neither environmental nor workers’ rights campaigners can risk their arguments being co-opted in this manner. Nor is the divide between environment and workers’ rights that has sprung up a real one. This report challenges ‘planet versus workers’ as a false dichotomy and a fabricated divide that generates tension and division. By offering a thorough investigation of the systemic causes of the damage done by the fashion industry, we hope to bridge this divide and show how the current growth-at-any-cost model is the real culprit.

From growthism to degrowth

To avert ecological and climate breakdown we must actively replace fossil fuels with a rapid rollout of renewable energy, cutting the world’s carbon dioxide emissions in half within a decade and reaching zero emissions by 2050. This must be done in an equitable way, recognising that responsibility for emissions lies with Global North countries. It also means measures to eradicate energy poverty and to reduce consumption. This is very hard to do while we are, as a global community caught in the trap of ‘growthism’.

Economist and author Jason Hickel defines ‘growthism’ as the idea that all sectors of an economy must mindlessly grow all the time, regardless of whether or not a society actually needs them to, and no matter the consequences. It is a political ideology that has become a dangerous dogma.20

‘Growthism’ has led to unsustainable levels of energy and resource-use in Global North countries, which is driving ecological breakdown. As an alternative, ecological economists propose that we should decide what sectors we actually need to grow (for example public transport, healthcare or renewable energy), and which sectors are destructive and socially less-necessary – and so should be actively scaled down or ended entirely (sectors mostly organised around capital accumulation and elite consumption). This idea, of scaling down certain sectors and forms of production, is known as ‘degrowth.’

In English, ‘degrowth’ is not a word that makes immediate sense. It has its origins in Latin languages, “la décroissance” in French or “la decrescita” in Italian, which refer to a river reverting back to its normal flow after a disastrous flood.21

As an idea, degrowth critiques the capitalist drive to seek growth no matter the devastating cost to people or planet. As a movement, degrowth is calling for societies, both local and global, to prioritise social and ecological wellbeing instead of corporate profit, overproduction and excess consumption. Rather than aiming to reduce all forms of production, degrowth is specifically about reducing less-necessary forms of production and is targeted at rich Global North countries, as those most responsible for driving the environmental damage and the climate crisis.

In practice, this means democratically reducing the scale of industrial production in Global North countries, and instead prioritising care and environmental justice so that everyone can live well within planetary boundaries. Crucially, it means radically redistributing resources to make up for past and current harms, such as slavery, colonialism, land theft, wealth hoarding, and rigged debt schemes and trade rules. In this way degrowth is a means for people in the Global North to recognise and oppose the structures that continue to limit possibilities in the Global South.

As economist Tonny Nowshin explains: “Degrowth fundamentally embeds the discussion of giving back resources that are taken by extraction from the Global South to the Global North, including wages. Degrowth doesn’t only focus on production but also redistribution of produce and resources. From a social justice perspective, degrowth is one of the frameworks that needs to make sure we are decolonial and caring for everyone. It’s not only about giving people more material things to reach a basic standard of living, but also making space for other forms of wellbeing like social connection, community, producing differently and sharing.”22

Degrowth is not a recession or a plan to make workers and the poor pay the price of change, nor is there any space within the degrowth movement for critiques pushing right-wing, racist or sexist ideologies.

While the word degrowth may not trip off the tongue, as Degrowth.info states, this strange word is supposed to be a disruption – pointing to the end of business-as-usual and a horizon of opportunity for us all.

As the economist Samir Amin wrote: “Today, modernity is in crisis because the contradictions of globalized capitalism, unfolding in real societies, have become such that capitalism puts human civilization itself in danger. Capitalism has had its day.” 23

The fashion industry produces an estimated 100 billion items of clothing24

and 24.4 billion pairs of shoes25

every year. Even using the loosest definitions of what constitutes human need, fashion is an extreme example of a sector organised around socially-unnecessary production. This makes it a top candidate for an industry that could be degrown, while still meeting the need for high-quality clothing that is neither resource-intensive nor devoid of creative and aesthetic design.

But if the industry shrinks dramatically, the essential question is what will happen to the jobs of the tens of millions of people currently working in clothing supply chains – from farmers growing cotton, to factory workers, freight drivers, warehouse workers and shop staff?26

Is it possible to transform society to protect people and their livelihoods while degrowing the industry?

In January 2023, Kalpona Akter, Founder and Executive Director of the Bangladesh Centre for Workers Solidarity (BCWS), described factory workers’ lives as “still dire”, with workers caught between long shifts, poverty wages, and gender-based violence on the one hand, and increasing economic instability due to a recession and reduced orders on the other. With rising inflation, no wage increases for five years and increased job instability, basic necessities are becoming unaffordable for many. “Garment workers are in a very difficult situation in terms of buying food,” Akter says. “Pretty much all of them are cutting back on food and that includes for their children as well.”

When workers lose their factory jobs, as so many did during the Covid-19 pandemic, they do not receive severance payments or unemployment support, and are unable to rely on public services. Akter describes fired workers as “going back to ground zero.” Nor are there other employment opportunities, except domestic work, which Akter describes as stigmatised even though it can occasionally pay better than garment work.

“I really don’t buy any of this discussion about green economies without workers’ voices and without worker protection for the wages,” Akter says, in a strong response to people who argue or infer that garment jobs are disposable. Akter describes a situation where people talk about fast fashion and creating carbon-free economies, but never think about the workers. “Making a carbon-free economy, or a green economy, or a Green New Deal or whatever you want to name it – where is the workers’ voice in that?” Akter asks. “If someone comes and talks about a green economy and says here is the workers’ voice then that is fine, otherwise I don’t validate any of these discussions.” “If it does not involve workers then this process is not democratic,” Akter continues. “It should not be a top- down approach. It should be bottom-up, you need to hear us. You need to know how we will be impacted when you do this new deal.”

“We did not screw this up, we workers did not do anything,” Akter adds. “It is you people who wanted to have more clothes at less prices and who put us in a difficult situation with poverty wages and long shifting hours, and now you think you need to do something that will make a green economy but you’re not going to think about us? No, it should not be like that! We want to have our space at the discussion table and make sure we are not losing anything. Until then, don’t talk to us about green economies.”

There is no need to imagine how badly scaling back could go if done in an unplanned, undemocratic manner. During the Covid-19 pandemic, there was an unexpected but enormous drop in production, which spelled disaster for garment workers and their families. In one pandemic survey, the Worker Rights Consortium found that 88% of the workers they interviewed had been forced to cut back on food for themselves and their households due to loss of income.27

Similarly, research from the Asia Floor Wage Alliance concluded that during the pandemic, workers coped by engaging in their own mental and physical degradation and that the pandemic saw the “mining of workers’ bodies.28

In July 2021, the Clean Clothes Campaign stated that garment workers globally are owed US$11.85 billion in unpaid income and severance pay, from just a single year of pandemic upheaval during March 2020 to March 2021.29

Since the pandemic, the industry has been impacted by continued economic instability and the global cost-of- living crisis, leading to more hardship and uncertainty. This series of global shocks illustrates an important point about the structure of not just the fashion industry, but of the global economy.

These crises are gendered. Ayomi Jayanthy Wickremasekara works at the Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union (FTZ&GSEU) in Sri Lanka, where community soup kitchens have been started in response to more and more garment workers becoming malnourished. “They have only one meal a day,” Wickremasekara says. “They don’t have a balanced diet, they face skyrocketing prices, and also they have no time to cook a balanced meal for themselves. There are so many single mothers with children. Those children become malnourished and the mothers become malnourished.”30

A branch of economics called unequal exchange theory states that economic growth in the rich Global North happens because vast quantities of human labour, land and natural resources are appropriated from the Global South. In the days of colonialism this appropriation was obvious – through taxes, slavery and invasions. Today, this extraction takes place via international trade deals and systems, which dictate differing prices and standards for different countries and regions.

14

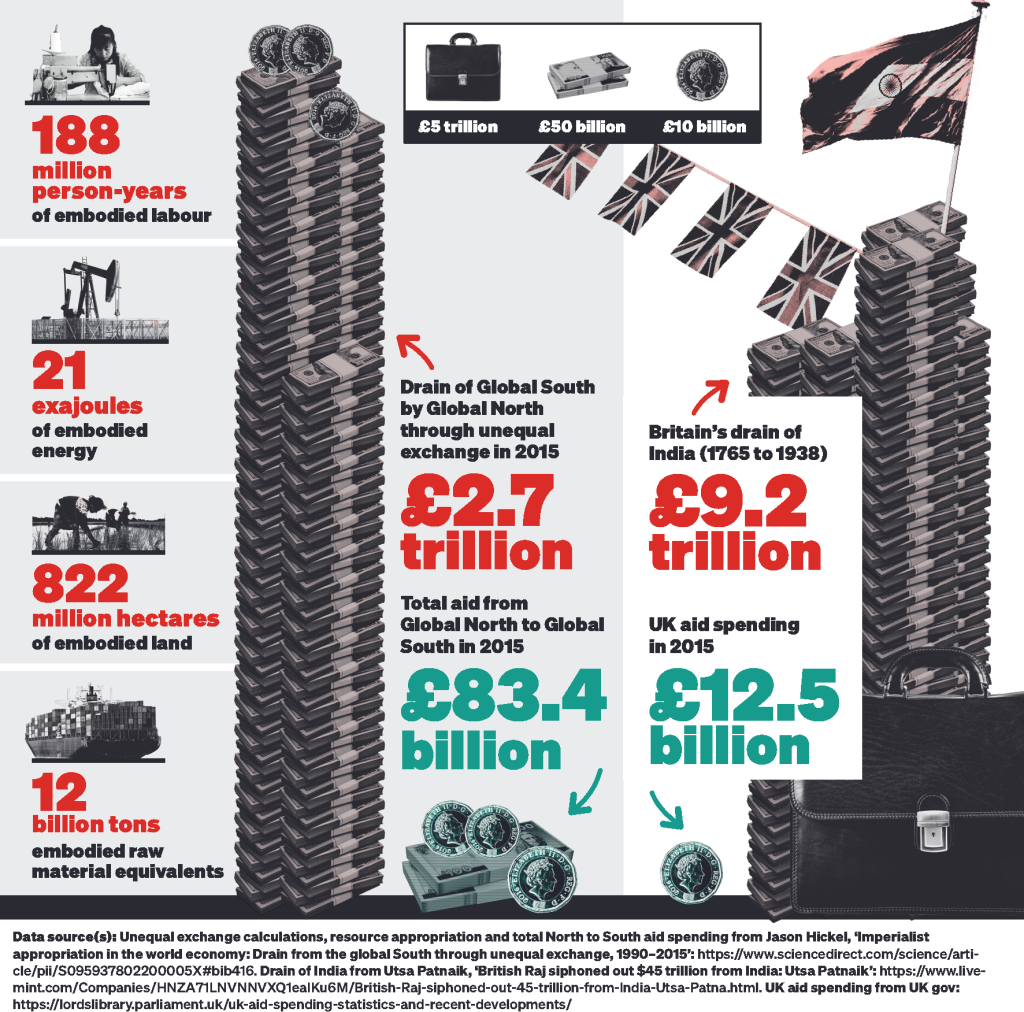

The scale of resource and labour extraction from the Global South to the Global North is vast. Jason Hickel led a research team which analysed data from 2015, and estimated this Global South extraction equated to 12 billion tons of embodied raw material equivalents, 822 million hectares of embodied land, 21 exajoules of embodied energy, and 188 million person-years of embodied labour. In a single year, that works out as value worth US$10.8 trillion15

– an amount of money that could end extreme poverty globally 70 times over.31

The team also concluded that from 1990 to 2015, this value drain from the Global South totalled US$242 trillion32

. This outstrips the aid sent by the Global North to the Global South by a factor of 30. Unsurprisingly, the paper concluded that “unequal exchange is a significant driver of global inequality, uneven development, and ecological breakdown.”

The geopolitical and commercial power of Global North countries and corporations enables them to cheapen the price of both natural resources and human labour in the Global South – and control national economies and global commodity chains such as garment production.

Economist Ndongo Samba Sylla has written about financial flows being less hampered today than during colonialism. “In the Global North, this pursuit of colonial economic logic entails an undermining of the previous socioeconomic and political achievements of working classes and hence a widening of within-country inequalities,” he writes. “In most of the Global South, next to the weakening of working classes power, neoliberalism has consisted in suppressing nations’ and people’s right to self- determination through the imposition of deflationary policies, forced ‘free trade’, privatisation and financial liberalisation.”33

Prices are always political

The price tags on the t-shirts, jeans, dresses, and jumpers in a Global North shopping centre do not represent the true value of these items, either in terms of material or labour. “The notion that prices are an accurate reflection of value is a very deep- seated assumption in capitalist ideology – and it is totally incorrect,” Jason Hickel explains. “There’s nothing natural about prices. Prices are an artefact of power.”

Just as the wages of nurses in the UK rise or fall depending on the bargaining power of working-class unions versus the government, the price of clothes in the UK is dependent upon the bargaining power of the countries, companies and workers that provide materials and labour to the garment sector. The value of a t-shirt on the UK high street should be seen as an effect of bargaining power, rather than a sign of the value of the product. “The cheapness is an illusion,” says Hickel.

Mountains of cheap clothes are possible because rich Global North countries have virtually all of the bargaining power in the world economy – which they use to maintain the status quo. The World Bank and the IMF – key institutions governing global economic policy – are deeply undemocratic, with unelected leaders from the US and Europe and voting systems that favour Global North countries. The US, Europe and the G8 nations34

control over half the votes – particularly unfair given that 85% of the world’s population lives in the Global South. By this count, in the IMF the vote of someone from Britain is worth 41 times more than that of someone in Bangladesh, despite colonialism supposedly having ended decades ago.35

“Inequality begets inequality,” Hickel continues. “Those who have power can determine the rules of the economy and they compress the prices of the weak. This is what occurs when it comes to the cost of labour in Bangladesh for example. There’s nothing natural about cheap labour in Bangladesh – it’s the effect of an imperialist economy over the span of several hundred years, which has worked specifically and actively to cheapen the price of Bangladeshi labour and resources.”

Inequality begets inequality.”

This vast inequality in the global economic system is the reason countries in the Global South are stuck servicing the Global North through exports and sweatshop labour. Export industries like garments are offered as economic miracles, along with coffee, tea and cotton, but they are a trap designed to maintain the flow of labour and raw materials from the South to the North. A combination of structural adjustment programmes, unjust trade rules, privatisation, austerity, and forced trade liberalisation meant avenues to sovereign economic development were cut off to Global South nations from the 1980s onwards when, as Hickel has written, rich Global North nations began to suspect that “the shift toward economic sovereignty in the South threatened access to the cheap labour, raw materials and captive markets they had enjoyed during the colonial era.”36

All of which prevents Global South countries from using fiscal-monetary policies necessary to mobilise production around socially useful work.

Instead, in order to earn foreign exchange, important for building infrastructure and importing food and fuel, Global South countries have to open themselves up to exploitation from Global North nations and corporations – opening the door to poverty wages, unsafe factories and a cascade of waste and chemical effluent.

Additionally, the cultural devaluing of clothes made in the Global South must be tackled. Price differentials in international trade deliberately keep the costs of fashion low but this is accompanied by a spectre of cheapness – of ‘cheap labour’ making ‘cheap clothes’ in ‘cheap countries’ and none of it being worth any more than what is paid. This extends to the four key fashion weeks taking place in the Global North, while Global South designers and brands are devalued. This means ending the racism that keeps countries like Bangladesh on the bottom rung of the fashion industry because the taught kudos is for clothing designed by Italians rather than Bangladeshis or Indians.

Radical change also means ending the patent system. The Global South contributes most of the world’s industrial labour and industrial production, and yet the overwhelming majority of both the credit and the profits go to the Global North. Much of this power is protected by the patent system, which allows big fashion to trademark their brands and aspects of the appearance of the products they sell. This cements the monopoly power of big fashion and means that despite clothes and shoes being made in the Global South with Global South materials and labour, the money is still hoarded by the Global North.

Organisations in the Global North hold 97% of all the patents in the world economy.37

“In a scenario where patents are abolished, we’d be buying our clothes directly from Bangladesh and they would accumulate the profits there,” argues Jason Hickel. “Were it not for patents, Bangladeshi manufacturers could also sell their products under the name Zara or H&M and therefore achieve whatever final price prevails in markets for those goods.”

All of this underlines the severe injustice of Global South dependency upon the North for its dollar earnings, and begs the question – why should Global South countries remain subordinate partners within global supply chains?

“Instead, Global South countries should pursue a more sovereign use of their productive capacity,” argues Jason Hickel. “This recession in the Global North has had devastating consequences for the poorest people on the planet in the Global South and that is not a situation that is tenable. That vulnerability should be reduced, and it should be reduced by organising production around sovereign economic development.”

Rather than being based on exports to the Global North, Global South production could instead be less exposed to global supply chains, organised around domestic requirements and regional trade to insulate economies from fluctuations in Global North demand, fluctuations that are only likely to increase as the climate crisis intensifies.

Amid the injustice is a place of great possibility. The countries of the Global South are not poor because they lack people to work, land, or natural resources, but because all their labour and resources are organised around the economic interests of the Global North, which has the power to maintain this imbalance. What we must do is imagine what could be achieved if the Global South stopped servicing the Global North. What might Bangladesh look like if its productive capacity were not organised around the economic interests of the rich world?

Imagine the potential of 188 million person- years of embodied labour and 822 million hectares of embodied land being put into something other than producing exports such as clothing, electronics, coffee, or cotton. It is here that the possibility of a society built upon care, craft, culture, public services and regenerative agriculture becomes a very real possibility.

Why do people work?

In the fashion industry, factory jobs are notoriously low-waged. People work to meet their basic needs and yet even their basic needs are not met. Take this snapshot from Shivakumar: “I have met workers who have spent forty years working in the industry, the second generation of their family is now in the industry, they’re producing for global brands and yet they cannot afford to build a toilet in their house.”

Similarly in Sri Lanka, where from 2022 onwards a national debt crisis has caused havoc across society, garment workers face great hardship. “The majority of garment employees are migrant workers and female,” says Anton Marcus, Joint Secretary of FTZ&GSEU. “Most of them are the breadwinners of their families but they do not earn enough income to support their family as well as themselves, so they live in private boarding houses where the conditions are very bad and without basic facilities.”

“They didn’t have any income in the village area and therefore in their family they didn’t have a voice,” Marcus continues. “But when they started earning in the factories they had some income, and therefore a voice in their family.” This hard-won independence is being undermined by the financial crisis and the withdrawal of orders by multinational corporations.

The structures of the global economy currently stop Global South countries from deciding how they want to use their own productive capacity, but let us explore what it could look like if this kind of autonomy existed. We must first examine why people have jobs in the first place. Under capitalism, people work in order to pay for basic needs such as shelter, food, healthcare, clothing, education and so on, with the lucky ones also working to pay for leisure activities or to create savings. Shivakumar’s example of the Indian garment worker paid poverty wages to produce globally-recognised clothing illustrates how even basic needs are not met by a lifetime of work, with the real value of the job lying in what it produces, not what the worker earns.

This is an essential point for figuring out a degrowth transition – the central question at the heart of transforming an economy should be: what do we want our economy to actually be producing?

“When politicians call for job creation, they never specify that there’s a deficit of specific products that we urgently need to produce more of,” explains Hickel. “If, for example, there was a deficit of refrigerators then we should mobilise labour to make refrigerators. But it’s always just ‘we must add more jobs’ and so the question becomes why – what are we producing for? The answer is we’re producing for capital accumulation. It doesn’t matter what we’re producing, it only matters that we’re producing for capital.”

f this political position was rethought, rather than just having people producing endless garments to make profits for corporations, Bangladesh could be asking:

What do we need?

What do we want to be producing? What are we producing too much of? What are we not producing enough of?

This allows the conversation to be about real goods and services rather than abstract jobs or abstract levels of GDP. “GDP doesn’t really matter,” Hickel continues. “What matters is whether we are producing what our society requires – what people actually need to live good lives.”

If this is starting to sound difficult to achieve, it is vital to note that huge changes in the world of work are on the near horizon. Automation and artificial intelligence threaten the traditional world of work, and the pandemic has shown the insecure nature of so many sectors, from tourism and hospitality to manufacturing and construction. Similarly, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that productivity will be badly hit by temperature increases caused by the climate crisis, with the percentage of total working hours lost rising to 2.2% in 2030, a productivity loss equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs. The most vulnerable regions to this particular burden of increased heat stress are southern and South-East Asia, western and central Africa.38

Analysing work in a scaled-back fashion industry can be divided into two regions – richer nations in the Global North and the poorer Global South countries. Let’s look briefly at the Global North end of the fashion supply chain, where hundreds of thousands of people are also trapped by low paid jobs, in retail, warehouses, freight transport, merchandising, cleaning and internships – which are still often unpaid – alongside the millions of other jobs in the wider economy that are not truly enriching for the worker or for society at large.

The good news is that in Global North nations, ecological economists have a very simple solution. It starts with scaling back less necessary forms of production – identifying which industries are harmful or superfluous and not pouring resources into them. Once this has been achieved, there will be so many more available workers that everybody’s working week can be shortened from 47 hours to 30 hours or even 20 hours.

There’s no reason that anyone should waste their time engaged in the production of goods that are socially unnecessary and organised only around corporate profit. It’s not just a waste of resources and energy, it’s a waste of human lives.”

The hours of work needed to complete socially agreed upon tasks can then be distributed far more equally to eliminate the extremes of some people being hugely overworked and stressed, and some having little or nothing productive to occupy them. The other effect of this would be a dramatic increase in leisure time that people could fill as they wished. Unsurprisingly, a multitude of studies, from the USA, France and Sweden, have all shown that working less hours makes people happier and healthier, as well as boosting gender equality, both in and out of the workplace.39

The move to a shorter working week would also free up millions of hours for care work and restorative activities – time, for example, for looking after children or older relatives or friends, time for volunteering in the community, time for planting and caring for trees and plants and restoring waterways and habitats. This is also a vital part of delinking jobs from economic growth, which would allow us to abandon the idea that economic growth is the ultimate objective of human existence.

Another idea is the concept of becoming a society of ‘prosumers’, where people work half the week then use the other half to repair, produce, and share the goods we already have – completely independently of industrialised production systems. We have so much already in existence that repair of electronics, of furniture, toys, clothes must become a central part of an ecological economy.40

Central to this would be guaranteed jobs that provide a generous living wage. A climate job guarantee would provide everyone with the right to a quality job and the necessary education and training to work on socially- vital projects. Job guarantees are routinely hugely popular in polling.41

Advocates for such a move include US congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, who is a strong advocate for a federal job guarantee and has pointed out that economic justice has always been a core component of the fight for racial justice. Civil rights icons from Martin Luther King Jr to Sadie Alexander, an iconic Black US economist, all advocated for a job guarantee to address racial discrimination against Black workers while improving labour market conditions for all.42

Hand in hand with rearranging the economy around human need rather than profit accumulation, is the need to treat essential services as a public good rather than a commodity. When profit is no longer the point of transport, communication, and energy provision – let alone education or healthcare – everyone will have access to the resources that underpin a dignified life and well-being.43

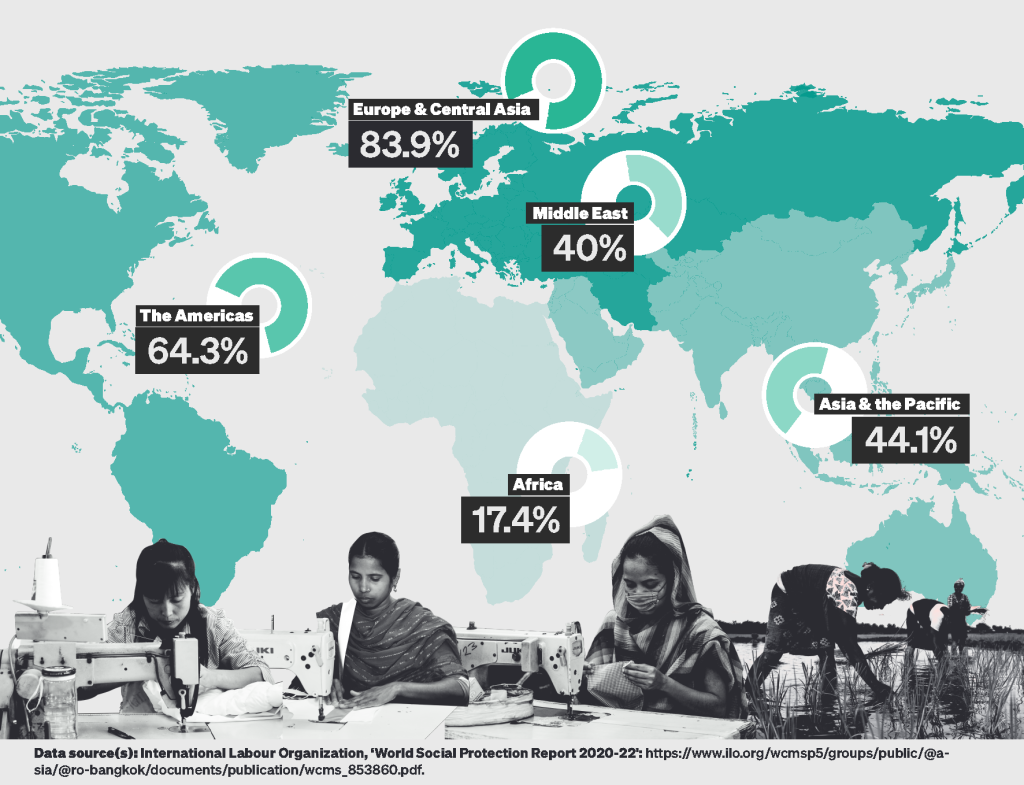

In the export economies of the Global South, any solutions must deal with the fundamental structural problems that inhibit these changes. In countries that have been deprived of their own resources and labour, leaving them unable to fully invest in public services, and where the basic necessities of life such as health and education have to be paid for at point of use, there is not a safety net for anyone who loses their ability to earn a wage. Research from the ILO found that as of 2020, 53.1% of the world’s population – as many as 4.1 billion people – are denied any kind of social protection benefit. There are significant inequalities across and within regions; coverage rates in Europe and central Asia (83.9%) and the Americas (64.3%) are above the global average, while Asia and the Pacific (44.1%), the Arab states (40.0%) and Africa (17.4%) are far more unequal.44

These structural issues must take priority, as any shift to a lower-impact economy in the Global North will create huge changes in employment in countries where there is significant poverty. Billions of people cannot and must not be left excluded from the basic foundations of a dignified life.

Kalpona Akter says there is currently not much discussion in Bangladesh of what kind of livelihoods garment workers could move to if the industry were to be degrown. “We know it’s a huge deal but there is no precaution from the government nor from the manufacturers or civil society. I think we need to worry about it – if out of the blue our workers start losing their jobs, there is no alternative industry ahead of them at this moment.”

Once again, we return to the issue that there is nothing natural about this existing poverty. Global South countries which are poor, are not poor because of a deficit of labour or resources – in fact they are often very rich in these things. The problem is that labour and resources are mobilised overwhelmingly around production for global supply chains which primarily service the profits of major corporations in the Global North, and which facilitate consumption and growth in those economies.

If out of the blue our workers start losing their jobs, there is no alternative industry ahead of them at this moment.”

The challenge then becomes how labour and resources can be mobilised around necessary production to meet local needs. For every region, country and community there will be different answers to what would be a better use of people’s time than stitching clothes for billionaires, but as Hickel says: “Every unit of labour that’s presently devoted to fast fashion could instead be reorganised around producing decent housing, or electrification, or healthcare, or schooling or whatever it might be.”

In Bangladesh, Akter is very clear on one thing that must be at the forefront of any transition: “I’m here to work on any kind of deal if it says that our workers will be getting a living wage. Why? At present in a family of four, all four people need to work because the income from one or two persons is not enough for the family.” The key factor to meeting job losses is a living wage, which means one or two people working can provide for their family.

The question of alternative jobs for garment workers has been on Akter’s mind since the pandemic decimated the industry. “The government should have vocational training in high-skill industries, and we should target our home market as well as export,” she says. “If we have a living wage and can create an alternative job market that could be high tech or agriculture, that way we can save these workers, otherwise we really don’t know what will happen.”

The options for a climate job guarantee, complete with education and training, are endless – the vital work of building a sustainable world includes; improving housing infrastructure, renovating and insulating homes, building ecological transport systems, energy network transformation, developing and installing renewable energy systems, restoring forests and ecosystems, developing permaculture projects, meeting human care needs, disaster relief work, building flood defences, pollution clean-up, urban planning and community restoration. A free and fair system that allows the Global South to properly use its own labour, land, people and resources for the common good, rather than multinational profit-generation will end the artificial scarcity of jobs and income that keeps so many people poor and dispossessed.45