Toxic harvest: fossil fuel pesticides on our plates

Not only is the industrialised global food system driving the climate crisis, it is pushing millions of small-scale farmers across the Global South into poverty – while making vast profits for a handful of corporations. Fossil fuels are used in every step of food production and distribution; from growing food, to packaging, shipping, consumption and waste – and we need to start paying attention. The industrial food system accounts for 15% of fossil fuels consumed globally each year1 – with that figure predicted to keep growing. Oil and gas corporations are now shifting their investment focus towards sectors connected to the industrial food system.2

Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron, among other fossil fuel polluters, are investing heavily in the production of agricultural chemicals, or ‘agrochemicals’, such as toxic pesticides and fertilisers.3 Agrochemicals are petrochemicals – chemicals derived from oil, gas, and coal – with fertilisers and pesticides used in industrial farming – together with plastics – counting for 75% of all petrochemical production. By 2026, petrochemicals are set to account for two-thirds of the growth in global demand for oil.4

Rich fossil fuel corporations have the power to influence global food policies and negotiations in their favour; from lobbying national governments to influencing UN Climate Summit (COP) negotiations. 1,733 fossil fuel lobbyists attended COP29 in November 2024, outnumbering delegations from almost every country.

What are agrochemicals?

Agricultural chemicals known as agrochemicals — or ’agrotoxins’ to many peasant movements in the Global South — include synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides. Specifically designed for producing food on an industrial scale, agrochemicals maximise crop yields by fertilising the soil or killing pests and weeds – but come with serious consequences for the planet and human health.

Nitrogen, for example, is a vital nutrient for plant growth, and is often added to fertiliser. Traditionally, soil would be fertilised with nitrogen by adding composted organic matter, or by planting pulses (such as chickpeas, beans, peas and lentils), which convert or ‘fix’ nitrogen gas from the air into a form of nitrogen in the soil.

However, since the end of the Second World War, industrial-scale farming has switched out traditional organic fertilisers for synthetic nitrogen-based fertilisers – which are easier to use at scale. Synthetic fertilisers are produced using gas or coal, often imported from China, Russia and India. Worse still are synthetic pesticides – used to control pests and weeds – which contain ingredients derived from fossil fuels and are highly toxic – with devastating impacts on soil fertility, biodiversity and human health.

How did we get here?

Food production on the industrial-scale seen today can be traced back to the post-Second World War era, when chemical manufacturers repurposed chemicals used in the war – including deadly nerve gases – for agricultural use.

During the 1950s, high-yield crop varieties were introduced to replace traditional seeds – however, achieving these high yields depended on using costly synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. Crops were often grown on vast plantations of a single variety – monocultures – which destroys biodiversity, a practice still in place today. This industrialised method of producing food saw land and power consolidated into fewer and fewer hands.

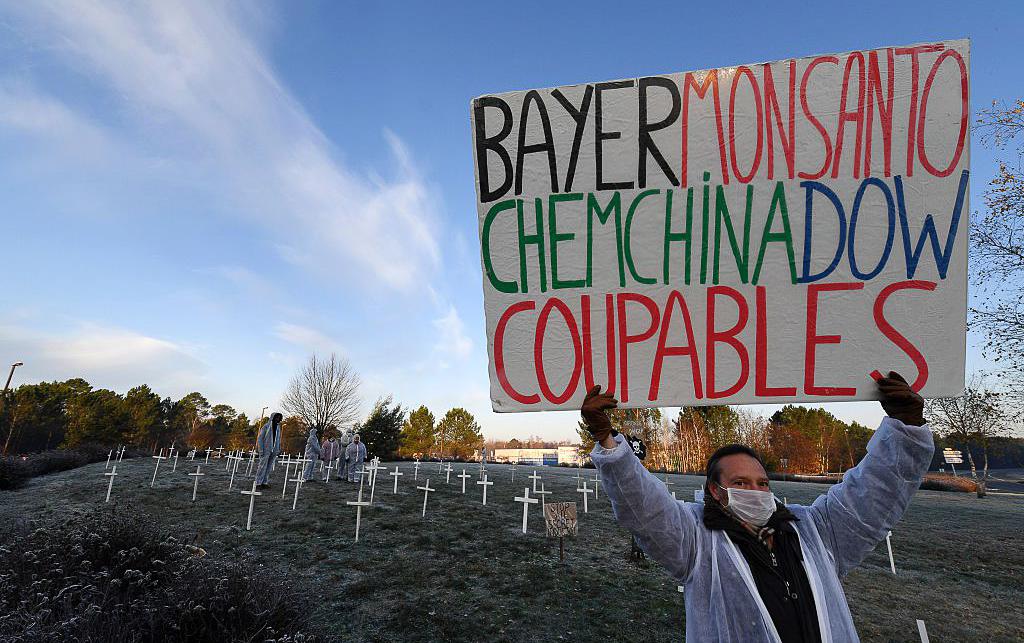

Today, control over the global food system rests with a just handful of vast, powerful agricultural corporations – which maintain monopolies over specific sectors, such as the production of seeds or agrochemicals. Just a few corporations control the entire food supply chain, which is now heavily reliant on fossil fuels – to create fertilisers, pesticides, and as fuel for machinery.

While this model may have served its purpose in post-Second World War reconstruction efforts, the industrialisation of our food systems has meant more energy, more chemicals and more plastics are needed to produce, package and ship food. This is having a significant long-term impact on the environment, while jeopardising the economic survival of thousands of small-scale farmers worldwide.

Toxic to the planet and human health

Constant exposure to harmful agrochemicals is having a major impact on small-scale farmers’ right to health: from Bangladesh to Paraguay, from Kenya to Brazil, toxic pesticides have caused cancer, interfered with human hormones, and damaged people’s reproductive systems.5 War on Want’s partners, peasants’ movements, trade unions and organisations across the world are campaigning about the dangers of fossil-fuel based agrochemicals.

Today, the use of highly hazardous pesticides is still legal in Bangladesh. One of these pesticides – paraquat – is recommended as a weed killer for use in tea, rubber, rice, and banana plantations. If it is inhaled or ingested, even in small amounts, paraquat can cause coma, organ failure – and ultimately death – within hours or days.

Paraquat has been banned in the UK since 2007 as a result, but the UK still produces and exports pesticides – including paraquat – to Global South countries where regulations are weaker.6 The double standard of many Global North countries — banning toxic agrochemicals at home, while exporting them abroad — is deeply unjust.

Farmers’ lands and livelihoods

Fossil-fuel-based pesticides and fertilisers are having a devastating impact on biodiversity, including by damaging soil health, and disrupting natural processes of pest control. Over time, this leads to soil becoming increasingly reliant on synthetic agrochemicals to keep producing food, which in turn makes farmers more dependent on the corporations that produce these agrochemicals.

Farmers’ dependency on agrochemicals, such as pesticides and fertilisers, increases their reliance on other agricultural essentials, such as seeds. Monsanto – one of the biggest agrochemical corporations – has, for decades, produced and sold a product called RoundUp Ready, which is a package of genetically modified seeds (usually soya), combined with the agrochemical glyphosate (a fossil-fuel based pesticide). Plants grown from these seeds cannot reproduce – their seeds will not grow into future plants – and toxic glyphosate is the only pesticide that works with this variety of herbicide-resistant seeds. This means that farmers have no choice but to rebuy this package every year, forcing smaller-scale farmers into debt, while wrecking their land and health.

The solution: peasant agroecology

To ensure the health of our future food system – and the farmers and lands that produce our food – we must transition away from a fossil-fuel-led industrial agriculture towards farming that centres farmers and workers’ rights and preserves biodiversity; also known as agroecology.

Peasant agroecology is key to food sovereignty – the farmer-led movement to put power over agriculture back in the hands of people. Food sovereignty emphasises the rights of smallholder farmers to land, water, and health; while promoting alternative economies based on principles of solidarity, to ensure that farmers and food workers receive fair prices and equitable treatment for their work.

In Bangladesh, our partners the Bangladesh Agricultural Farm Labour Federation (BAFLF) and Jatiyo Kisani Shramik Society (JKSS) are working to gradually transition smallholder farmers towards agroecology. Through workshops and training sessions with farmers, our partners have, for years, been encouraging local seed use and preservation, and farming without the use of fossil-based pesticides, while campaigning for a transition towards food production based on agroecology and food sovereignty in Bangladesh.

A global, just transition away from fossil-fuel-based agrochemicals requires a carefully planned, gradual, and mutually agreed phase-out, developed in collaboration with food producers and supported by clear, economically and socially affordable alternatives.

It takes time to shift food systems – and peasant movements know this. But the evidence supports them: more and more research is showing that agroecology, built on the principles of food sovereignty, works.7 Agroecology would allow food to keep being produced on the same scale, while reducing poverty and inequality. It puts food producers — rather than big corporations — at the heart of the food system8 and leads to fertile soil, healthier food and farms that are resilient to climate disasters.

Governments must stop supporting fossil fuel and large agricultural corporations by cutting tax-payer handouts – subsidies – and stopping tax breaks. Instead, this money should go towards financing peasant-led agroecology, with enough time allowed for a proper transition to fairer food systems, while public policies are put in place to prevent large corporations from dominating and monopolising our food systems.

Recognising the role of food sovereignty and agroecology as fundamental to public policy is the first, essential step to achieve a just, equitable and ecological transition towards greener, fairer societies and economies: a world where biodiversity is protected, and nutritious food is available and affordable for all.